1. Bacterial disease and antimicrobial resistance challenge

Bacterial infections represent one of the most persistent challenges in monogastric production, affecting both animal health and food safety (Mak et al., 2022). A wide range of pathogens (e.g., Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica, Campylobacter jejuni/coli, Clostridium perfringens, etc.) can colonize the gastrointestinal tract or other tissues (Mancabelli et al., 2016; Oakley et al., 2014; Kumar et al., 2018).

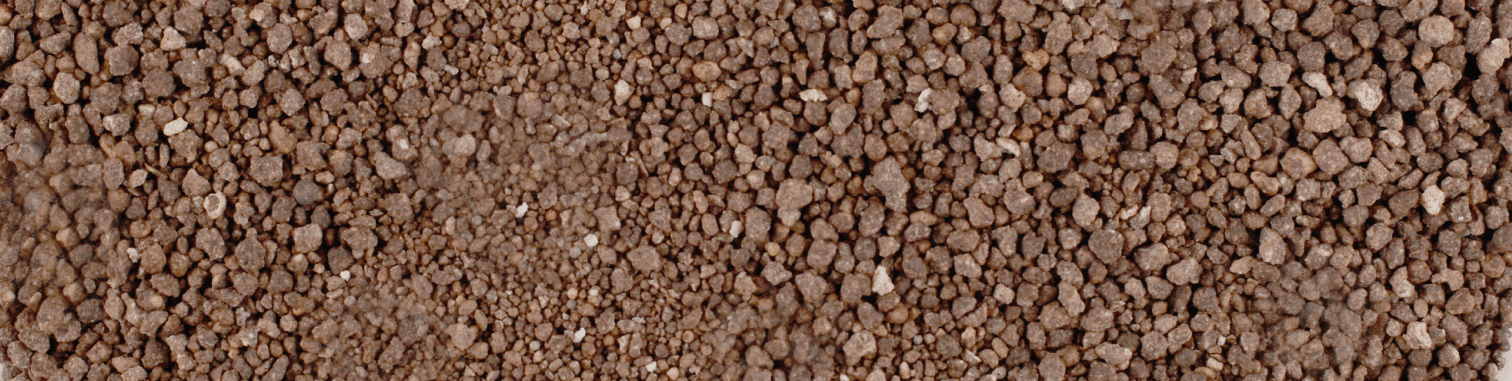

These organisms vary in pathogenicity and impact: some primarily compromise gut integrity and nutrient absorption, while others cause systemic infections or pose zoonotic risks (Figure 1) through carcass and egg contamination.

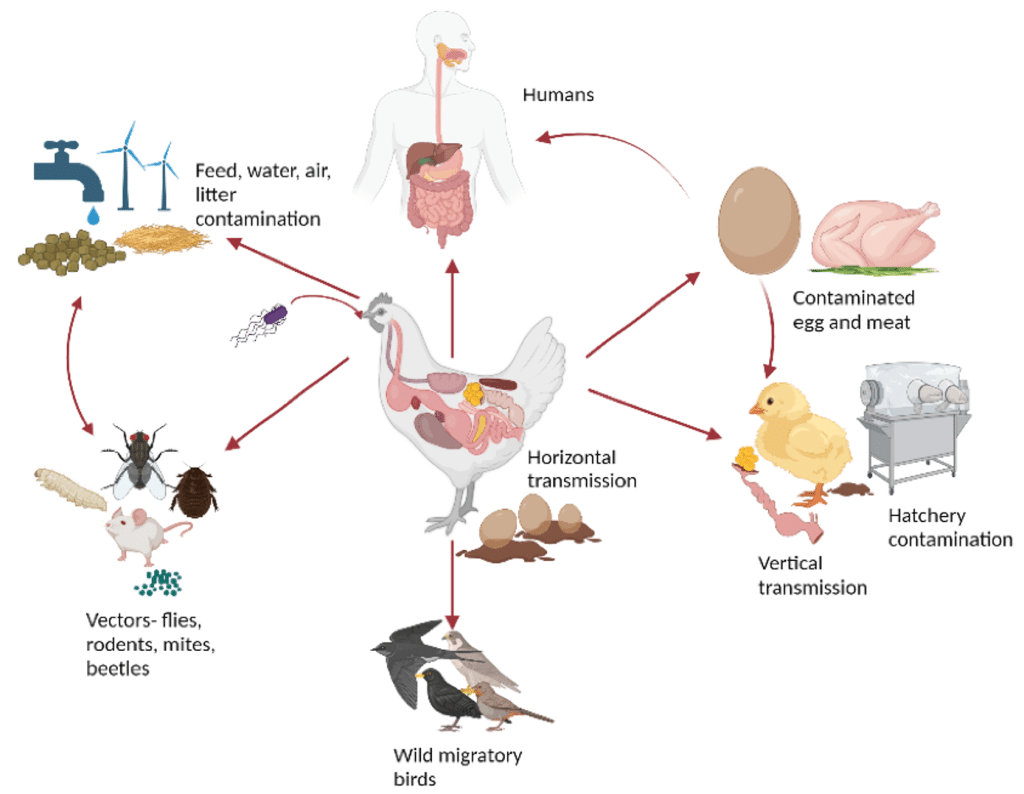

Historically, antibiotics were widely used to control these diseases and improve productivity (Mak et al., 2022). However, such practices have contributed to the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), now recognized as a global threat to animals and human health (Figure 2).

As animal production systems reduce antimicrobial use to address AMR concerns, producers face new challenges: subclinical bacterial infections often remain undetected, yet they divert nutrients toward immune responses and tissue repair, reducing feed efficiency and profitability (Shen et al., 2010; Marcq et al., 2011; Quinteiro-Filho et al., 2012; Remus et al., 2014). This reality underscores the need for integrated strategies that maintain intestinal health and control bacterial populations without relying on antibiotics.

Figure 1: An example with Salmonella spp. An overview of the various transmission routes. Created with BioRender.com

Figure 2: Antimicrobial resistance in livestock, humans, and environment. Adapted from Silva et al. (2023). Created with BioRender.com

2. Gut integrity, microbiota balance, and why inflammation is costly.

The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) plays a central role, acting as both a nutrient absorption system and a barrier against pathogens (Pan, D., & Yu, Z., 2013). Its integrity depends on a balanced microbiota, efficient immune responses, and a functional epithelial layer (Rodríguez, 2023). The gut microbiota can be divided into luminal populations, residing in the digesta, and mucosal populations, attached to epithelial cells. Both communities interact dynamically and can be altered by diet and environmental stressors.

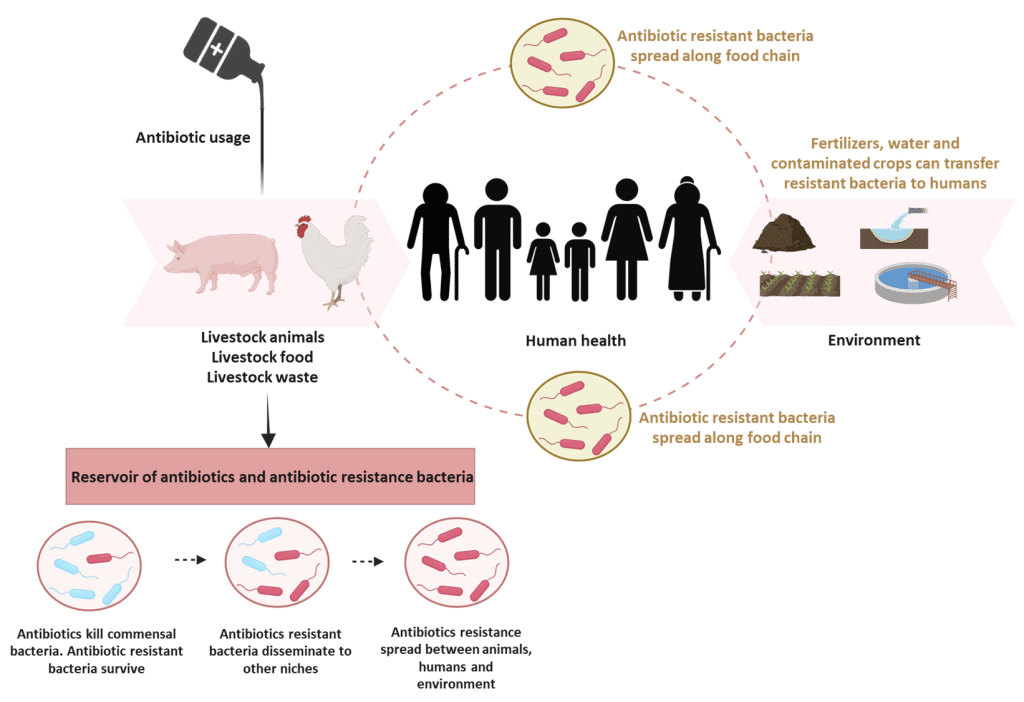

When intestinal integrity is compromised, homeostasis is lost, leading to dysbiosis, mucosal barrier leakage, and inflammation (Dridi and Scanes, 2022; Eveaert, 2025). Initially, inflammation is protective, but chronic activation diverts energy away from growth toward immune function and tissue repair (Teeter RG., 2007). It is estimated that to meet the amino acid requirements for the synthesis of each milligram of immune response protein, 2.33 mg of muscle protein are catabolized (Reeds et al., 1994) (Figure 3).

This shift increases maintenance requirements and reduces feed intake and daily weight gain, impairing feed conversion efficiency (Latshaw, 1991; Shen et al., 2010; Marcq et al., 2011; Quinteiro-Filho et al., 2012). Subclinical enteric disorders are particularly concerning because they persist undetected, causing cumulative losses in productivity and profitability.

Figure 3: Inflammatory cascade in chickens: pathogen invasion activates immune cells (macrophages), triggering cytokine release (IL-1, TNF, IL-6). These signals stimulate the liver to produce acute-phase proteins, while systemic effects include muscle protein breakdown for amino acid supply and fever induction via hypothalamic regulation. Adapted from Klein (2020); Dridi and Scanes (2022); Schothorst feed research (2024). Created with BioRender.com

In intensive systems, where animals are exposed to crowding and stress, these conditions are amplified, creating an environment favorable for opportunistic pathogens.

3. Relevant pathogenic species

Animal microbiota can also harbor commensal and pathogenic species (e.g., Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica, Campylobacter jejuni or Clostridium perfringens) (Dridi and Scanes, 2022). These pathogens are frequently associated with enteric or systemic infections and represent major concerns for animal health and food safety. Moreover, their complex cell surface confers intrinsic resistance to multiple antibiotics, complicating control strategies (Miller, 2016).

Common conditions in intensive poultry systems, such as high stocking density, environmental stress, and dietary imbalances, favor the colonization of these pathogens in the gastrointestinal tract. While some infections are acute and easily detected, many occur subclinically, reducing growth performance and efficiency without overt clinical signs. This complexity underscores the importance of preventive strategies that address both gut health and pathogen control.

3.1. Predisposition factors and subclinical impact

Several factors predispose animals to bacterial overgrowth and disease. Among these, coccidia (Figure 4) is a primary trigger, damaging the intestinal mucosa and creating conditions favorable for Clostridium perfringens proliferation and toxin production (Rodríguez, 2023).

Subclinical coccidiosis is highly prevalent, with reports indicating an average of 34.8 % in broilers (Gazoni et al., 2021) and an estimated 9 % production loss in European systems (Teeter RG et al., 2008). Even mild lesions can impair nutrient absorption, reduce energy intake, and worsen FCR. Additionally, late coccidia challenges (broilers from 35–42 days) have the most severe impact, reducing average daily gain by up to 25% and increasing FCR significantly (Teeter RG et al., 2008).

Figure 4: Eimeria tenella sporulated oocyst (You M, 2024)

3.2. Performance and economic impact of 2 enteric pathogens

Avian pathogenic E. coli (APEC) and Clostridium perfringens are two of the most economically significant enteric pathogens in poultry production, responsible for colibacillosis and necrotic enteritis (NE), respectively. Both pathogens are associated with impaired growth performance and increased mortality in commercial flocks (Mak et al., 2022) (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Avian pathogenic E.coli (APEC)

Colibacillosis leads to systemic conditions such as colisepticemia, aerosaculitis, peritonitis, cellulitis, and salpingitis (Mak et al., 2022).

- Mortality rates in young birds range from 20 % to 53.5 %, while survivors often exhibit reduced body weight (−2 %), impaired FCR (−2.7 %), and up to 20 % lower egg production and hatchability (Olsen et al., 2012; Nolan et al., 2020).

- In Brazil, slaughtered houses reject up to 45.2 % of carcass due to cellulitis, representing annual losses of approximately $10 million (Fallavena et al., 2000).

- Additionally, APEC strains are commonly associated with high levels of antimicrobial resistance, complicating treatment and control strategies (Van Limbergen et al., 2020).

Clostridium perfringens causes necrotic enteritis (NE), which may be clinical or subclinical (Hargis, 2023) (Figure 6).

- This Gram-positive bacterium is a commensal organism present in 75–90% of birds, but under favorable conditions, it can proliferate and causes necrotic enteritis.

- In poultry, clinical NE may result in daily mortality rates of up to 1%.

- Subclinical NE, estimated at 20% prevalence, can reduce body weight by 12% and increase FCR by 10.9% (Wade and Keyburn, 2015; Skinned et al., 2010).

- The global economic impact of NE is estimated at $5–6 billion annually (Wade and Keyburn, 2015).

These figures underscore the hidden cost of subclinical infections, which often remain undiagnosed yet significantly compromise profitability.

Reducing antibiotics in animal production has driven the search for alternatives, including functional raw materials that may contribute to microbial modulation and support gut integrity.

Figure 6: Clostridium perfringens

4. Functional phosphate effects: Calcium Humophosphate and its impact on bacterial proliferation

Calcium humophosphate (HumIPHORA) is a functional phosphate, obtained through the reaction of phosphoric acid, calcium, and humic substances (HS). Its primary mechanism of action involves limiting the formation of insoluble complexes. Beyond this, its composition also confers secondary benefits on intestinal health.

In animal nutrition, HS have demonstrated antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties. Their ability to form protective layers over the intestinal epithelium helps prevent the adhesion and translocation of pathogenic bacteria and toxins, contributing to improved mucosal integrity (Arif et al., 2019; Domínguez-Negrete et al., 2019; Zanin et al., 2019). The integration of humic substances into mineral matrices such as calcium humophosphate may enhance their biological activity, supporting gut health and microbial balance in monogastric animals.

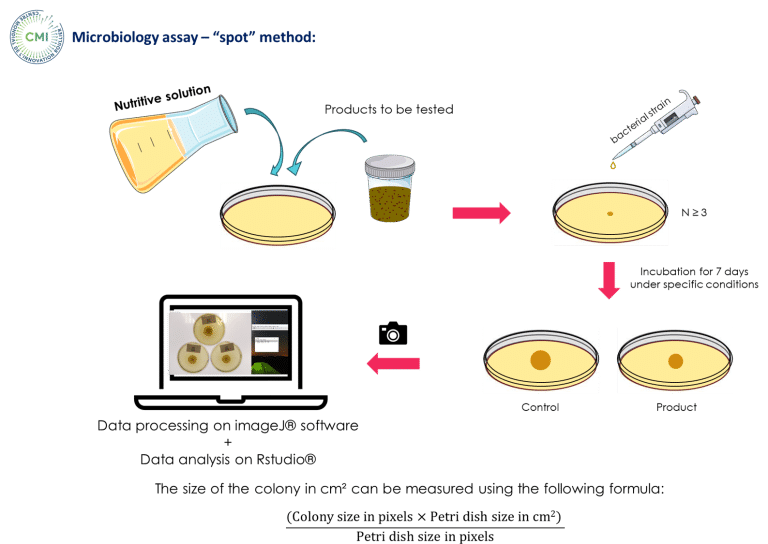

An in vitro trial was conducted at the Centre Mondial de l’Innovation (CMI) using the spot method to evaluate the antimicrobial potential of HumIPHORA versus a conventional inorganic feed phosphate source (monocalcium phosphate, MCP) (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Microbiology assay – “spot” method made in our in vitro trial (CMI, 2025)

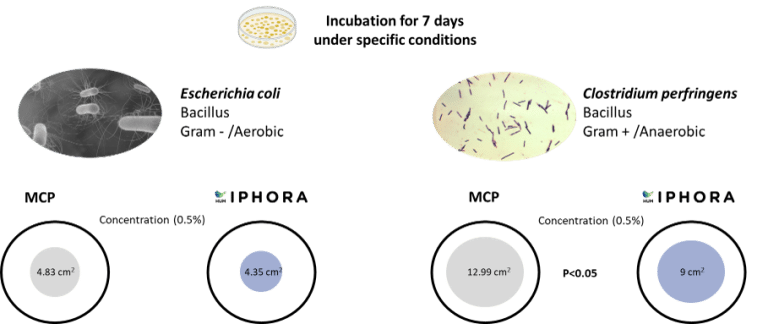

HumIPHORA exhibited stronger inhibitory effects against Escherichia coli and Clostridium perfringens compared to MCP (Figure 8). These results reinforce the microbiological relevance of calcium humophosphate and are consistent with previous in vivo observations in swine, where reduced diarrhea incidence was reported. In addition, field trials suggest that using HumIPHORA may have a positive effect on bird mortality. For example, in a broiler trial under heat stress, cumulative mortality from day 0 to 42 was 9.3% with HumIPHORA group compared to 14.5% with dicalcium phosphate. This effect may also be observed in chicks during the first days of life, when they are physiologically immature and more vulnerable to oxidative stress (Baeza & Coudert, 2023).

HumIPHORA shows promising antimicrobial activity and potential benefits on monogastric. These findings open perspectives for further validation through controlled in vivo trials and additional experimental performance studies.

Figure 8: Effect of HumIPHORA on bacterial growth (E. coli and C. perfringens)