1. Phytic acid role and relevance

Phytic acid (InsP6) and its salts (phytate), are natural compounds found in many plant-based ingredients, and it’s a major storage form of phosphorus in plant seeds and grains. As a result, phytate is present in monogastric feed diets, which lack the endogenous enzymes needed to break it down efficiently.

Phytic acid poses nutritional challenges, since it has a strong tendency to bind minerals as well as proteins, reducing their bioavailability.

Understanding the structure, role and impact of phytic acid is therefore essential to support sustainable feeding practices.

2. Phytic acid structure

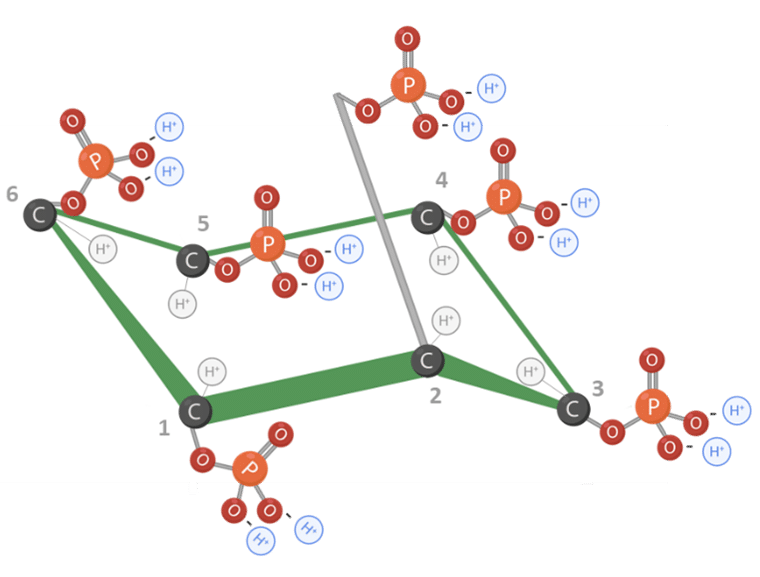

Phytic acid, chemically known as myo-inositol hexakisphosphate (IP6), consists of a ring-shaped molecule called myo-inositol to which 6 phosphate groups are attached, one on each carbon atom (Figure1) (FEDNA, 2021).

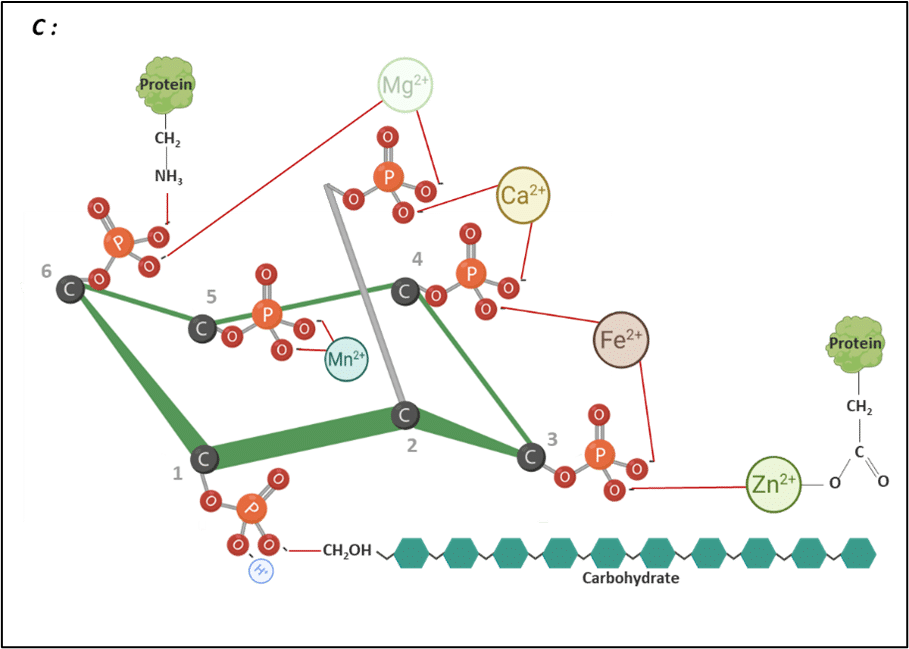

In plant ingredients, phytic acid rarely exists as a free acid. Instead it forms salts with minerals like calcium, magnesium, and potassium, or even with proteins and starches forming more complex structures. These salts are known as phytates or phytin (Outchkourov & Petkov, 2019; Humer and Schwarz, 2014).

Structurally, the phytic acid molecule contains 12 replaceable protons, which confer a high electronegative potential when exposed to pH values near neutrality. This makes the molecule highly reactive and unstable in its free form (Humer and Schwarz, 2014) (Figure 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Molecular structure of phytic acid. Adapted from Vieira et al., 2018. Created in BioRender.com

Figure 2: IP6 bound to different nutrients. Adapted from Vieira et al., 2018. Created in BioRender.com

3. Phytate in raw materials

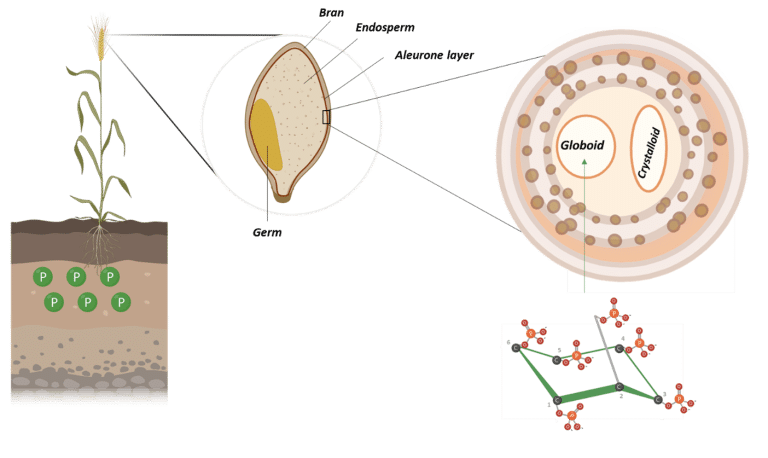

In plant seeds, phytic acid is the main storage form of phosphorus. It accumulates during seed development and is typically stored in specialized vacuoles called globoids (Figure 3) (Bohn et al., 2007; Kumar et al., 2019).

Figure 3: Phytate storage in wheat granules. Adapted from Freed et al., 2020. Created in BioRender.com.

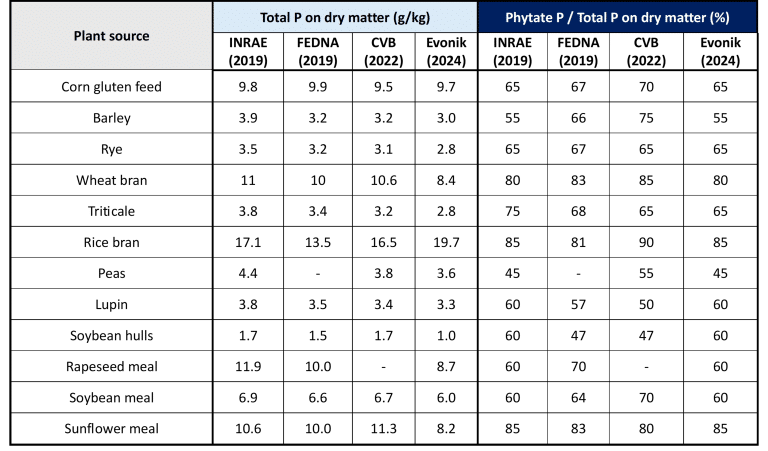

Phytate concentrations vary widely across feed ingredients. Around 50–80% of the total phosphorus in cereal grains and oilseeds exists in the form of phytic acid/phytate (Kavitha, 2016; Kumar et al., 2019).

Monogastric diets contain about 0.2 – 0.3% of phytate-bound phosphorus (InsP6-P), although its concentration varies depending on the raw materials used and their cultivation/processing conditions (Table 1) (Rodehutscord et al., 2016; Outchkourov & Petkov, 2019).

Table 1: Total phosphorus content and Phytate-P Proportion based on some feed ingredients.

Given the variability in phytate composition and its susceptibility to hydrolysis across different feedstuffs, it becomes essential to understand how phytate is broken down.

4. Phytate breakdown: Phytases and microbial activity

The hydrolysis of phytate involves the stepwise removal of phosphate groups from the InsP6 molecule, resulting in lower inositol phosphates such as InsP5, InsP4, and InsP3. This process can occur through 3 main sources of phytase activity: intrinsic plant phytases, microbial-mucosal phytases, and exogenous phytase supplementation (Humer and Schwarz, 2014; Rodehutscord and Rosenfelder 2016).

4.1. Plant phytases

Endogenous phytase activity in plants plays a key role in the initial breakdown of phytate. Cereals such as rye, wheat, barley, and their by-products exhibit high levels of native phytase, while legumes and oilseeds generally show lower activity (FEDNA, 2021). However, plant phytases are thermolabile, for instance, pelleting at temperatures above 85 °C may inactivate up to 74% of phytase activity (Outchkourov & Petkov, 2019).

4.2. Effect of the poultry gastrointestinal tract (GIT)

The digestive tract plays a role in the breakdown of phytate. The crop, while not a major site of absorption, may initiate phytate hydrolysis through microbial activity. Although the short retention time of digesta may limit enzyme action (Kerr et al., 2000; Witzig et al., 2015).

In the caeca, there is a highly diverse microbial community with substantial phytase activity. However, despite the enzymatic potential, the nutritional relevance of phytate hydrolysis in the caeca is limited (Zeller et al., 2015), and phosphorus released in the caeca is largely excreted due to the lack of post-ileal absorption (Son et al., 2002).

4.3. Exogenous microbial phytases

The use of exogenous microbial phytases has become one of the most effective strategies to enhance phosphorus bioavailability in monogastric nutrition (Kumar & Sinha, 2018). The stomach is the main site of phytase activity due to its low pH. Once the feed passes into the intestine, phytase activity declines due to reduced solubility of phytate and less favorable pH conditions (Kumar et al., 2019; Humer & Schwarz, 2014).

Phytase efficacy depends on pH and temperature stability, substrate affinity, resistance to proteolysis, gastrointestinal retention time, and dietary factors such as Ca:P ratio and phytate concentration (Kumar et al., 2019). Despite advances in phytase technology, complete dephosphorylation of IP6 to myo-inositol is rarely achieved (Menezes-Blackburn et al., 2015).

Understanding the enzymatic strategies to degrade phytate is essential not only for improving phosphorus utilization, but also for mitigating its antinutritional effect.

5. Phytate interactions with nutrients

Beyond its role as an organic phosphorus source, phytate can present antinutritional effects that compromise nutrient utilization in monogastric animals.

5.1. Phytate-Mineral interactions

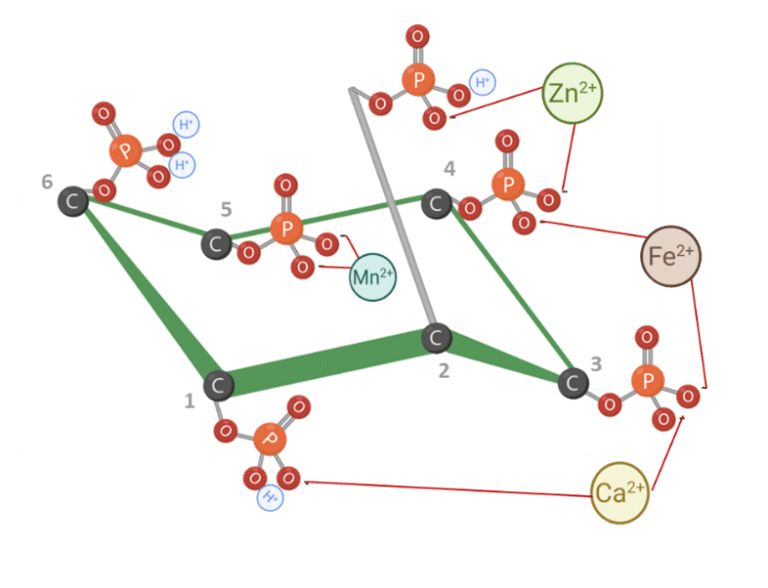

Phytate can interact with essential minerals (Figure 4). These interactions result in the formation of insoluble phytate–mineral complexes that are poorly absorbed in the intestine, reducing mineral bioavailability (Kumar & Sinha, 2018; Outchkourov & Petkov, 2019).

According to Cheryan (1980), the phytate’s mineral-binding follows a general order of stability: Zn²⁺ > Cu²⁺ > Ni²⁺ > Co²⁺ > Mn²⁺ > Ca²⁺ > Fe²⁺. This hierarchy reflects the varying degrees to which different minerals are affected by phytate chelation.

In order to achieve sufficient solubility of both minerals and phytic acid esters at a higher pH, early hydrolysis of phytate, ideally in the stomach, may be necessary to reduce complex formation and to enhance mineral absorption.

Figure 4: IP6 bound to cations. Adapted from Vieira et al. (2018). Created in BioRender.com

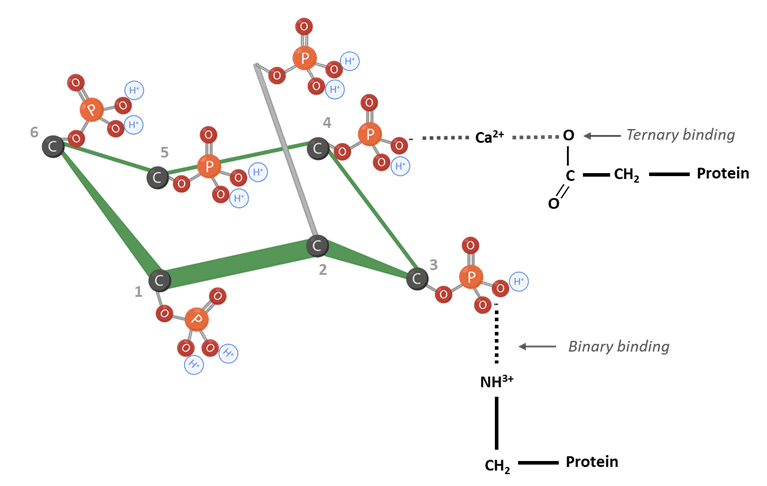

5.2. Phytate-Protein interactions

Phytate can impair protein utilization through the formation of protein–phytate complexes (Humer et al., 2014). At low pH values, phytate interacts directly with basic amino acids. As pH increases in the small intestine, phytate can form ternary binding with proteins and multivalent cations such as calcium (Figure 5) (Kumar et al., 2019; Reddy & Salunkhe, 1981; Nissar et al., 2017; Humer et al., 2014).

Figure 5: IP6 bound to proteins. Adapted from Morales et al. (2016). Created in BioRender.com

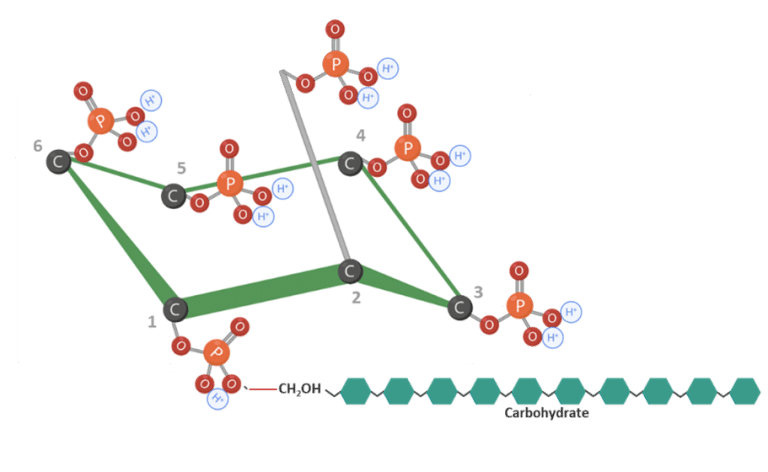

5.3. Broader nutrient interactions of phytate

Phytate can interact with carbohydrates by forming complexes with starch (Figure 6) (Kumar et al., 2019). Likewise, phytate can also interact with lipids reducing energy utilization (Humer & Schwarz, 2014; Camden et al., 2001).

Figure 6: IP6 bound to carbohydrates. Adapted from Vieira et al. (2018); Oatway et al. (2001). Created in BioRender.com

Finally, phytate strongly interacts with essential nutrients limiting their bioavailability and negatively impacting feed efficiency. While conventional inorganic phosphate supplementation can help to meet phosphorus requirements, it does not effectively counteract these broader antinutritional effects (Outchkourov & Petkov, 2019). However, new generations of functional phosphates have emerged, to counteract the formation of insoluble complexes.

6. Innovative functional raw material: Calcium Humophosphate – limiting phytate interactions

One of the remaining challenges in phytate degradation is minimizing the formation of insoluble complexes. In this context, calcium humophosphate (HumIPHORA) represents an innovative and functional approach. It combines phosphorus, calcium and humic substances—organic compounds with chelating properties that can interact with ions in the gastrointestinal tract.

HumIPHORA has the ability to bind divalent cations, such as the excess of calcium, reducing its interaction with phytic acid. This limits the formation of insoluble calcium-phytate complexes and keeps phytate in a more hydrolysable form. Consequently, phytase action is facilitated, improving the release and absorption of phosphorus from plant ingredients.

Unlike conventional phosphate sources, HumIPHORA interacts with nutrients in the gastrointestinal tract and counteracts antinutritional effects of calcium and phytate. Its inclusion in poultry diets represents a strategy to enhance phytate degradation and improve nutrients absorption—particularly phosphorus and calcium, which are critical for growth performance and skeletal development.

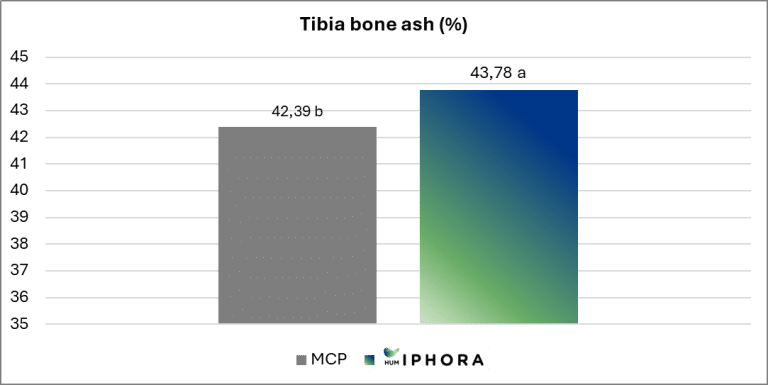

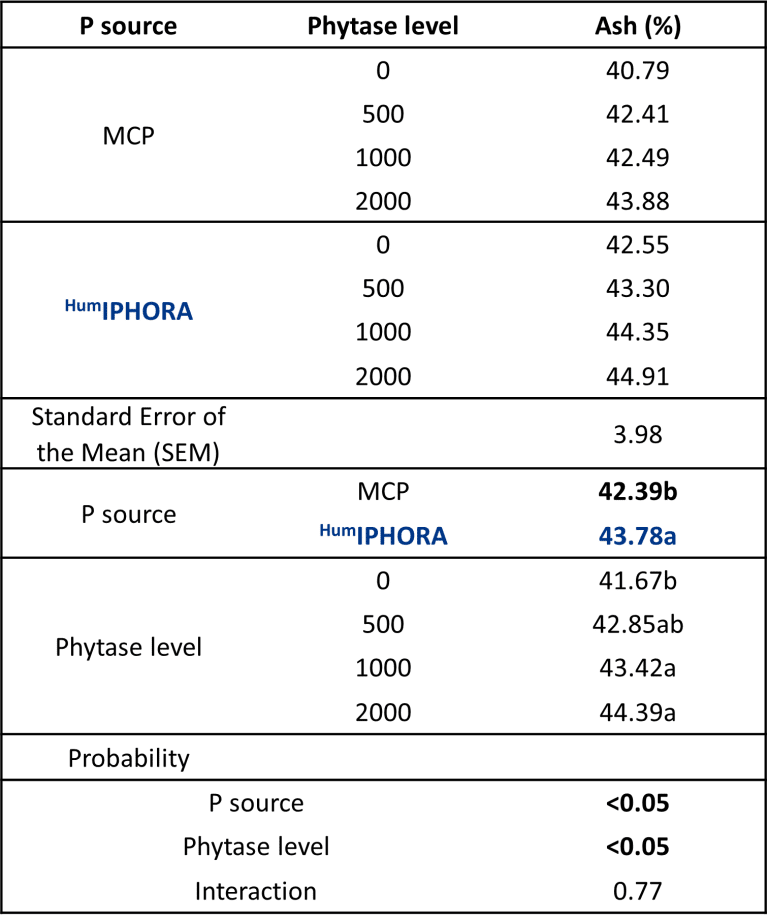

An experimental trial conducted in collaboration with the University of São Paulo confirms this effect, showing significantly higher tibia ash content in broilers fed diets containing HumIPHORA compared to those with monocalcium phosphate (MCP) (Figure 7). Tibia ash is a reliable indicator of bone mineralization, which reflects improved calcium and phosphorus retention and supports skeletal development.

Figure 7: Effect of the inclusion of HumIPHORA in broiler diets on tibia ash.